Shelley Jackson’s son is yet to finish primary school – but until recently, she worried he would be kicked out of school before that could happen.

Shelley would receive daily phone calls about her son’s behaviour.

The phone calls would tell her “he was dysregulated, he was out of class, he was up a tree”.

“The behaviour became worse and worse, and he was trying to abscond from the school,” she tells Sky News.

It seemed he was heading for permanent exclusion, which would have seen him “probably passed from school to school”.

Had that happened, he would have joined the tens of thousands of primary school children excluded each year.

School exclusions are at an all-time high, government figures show, with more than 85,000 primary-aged children excluded or suspended last year. Of those, 27,500 were aged six or under.

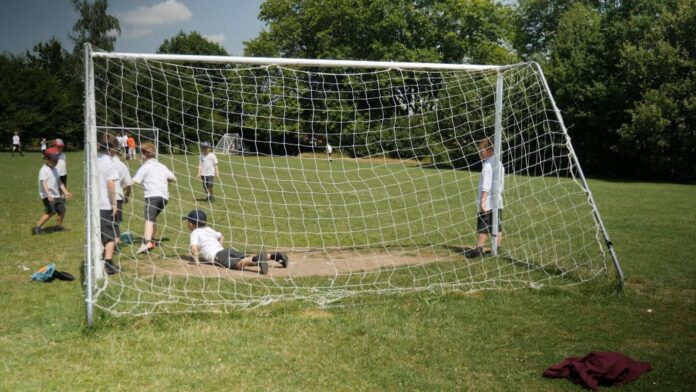

While many schools adopt a zero-tolerance approach to behaviour and discipline, at Templewood Primary School in Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, headteacher Katherine Martindill has taken the opposite approach.

Exclusions and suspensions are banned. They don’t work, Ms Martindill tells Sky News: “You are ultimately telling the children that they’re not valued. And then they go home.

“We can’t teach them when they’re at home.”

By keeping them at school, the school can give children “the tools to manage their behaviour”, she says.

“If we do not help them, then who will?”

Ms Martindill’s policy marked a turning point for Shelley’s son – and for other families who spoke to Sky News.

‘His self-esteem had already taken a battering’

Sarah Buxton’s son found school a “distressing” place.

“He would seem quite angry, possibly throwing chairs and up-ending tables.”

The year two pupil was “already quite down on himself”, she tells Sky News.

“His self-esteem had already taken a battering… If he had been rejected from the school as well? I just dread to think what that would have done to us, to him, to me.

“I just think it would have been extremely hard.”

Luckily, the school’s policy meant that wasn’t on the cards, and instead he and his family were supported.

“The hub and the support we have received has changed our lives around,” Ms Buxton says.

From lashing out to being ‘full of beans’

Karlie Greenleaves and Barry Hopkins have seen a marked change in their year three son since the no-exclusion policy was implemented.

“He now loves school and is ready in the morning – for him it’s all about a routine.

“Before he would be lashing out and not know how to communicate.”

They say the difference comes from him being able to recognise how he feels loved.

Read more:

Register of ‘ghost children’ missing from school to be created

Report calls for primary school exclusions to be banned

‘Something is going seriously wrong’

The overwhelming majority – 97% – of primary school-aged children who are excluded have special educational needs and disabilities, Sophie Schmal, of children’s early intervention charity Chance UK, tells Sky News.

“Something is going seriously wrong” for so many six-year-olds to be suspended and excluded from education, she says.

“We can see how detrimental suspensions and exclusions can be for long-term outcomes for children.

“They are more likely to be suspended or excluded later in life. They’re more likely to disengage from education.”

Chance UK’s research into exclusions shows more than 90% of children excluded at primary school do not pass GCSE English and maths.

Schools excluding children need ‘more accountability’

Ms Martindill says there “needs to be more accountability for schools using exclusions”.

It’s up to headteachers to decide their school’s policy on exclusions – but if they decide to do away with them, they need the funding to put other support measures in place.

“Children do not succeed academically if they are not happy,” she adds.

The new government’s plan to tackle poor behaviour

Responding to the Department for Education figures on exclusions, minister Stephen Morgan said they show the “massive scale of disruptive behaviour that has developed in schools”.

“We are determined to get to grips with the causes of poor behaviour: we’ve already committed to providing access to specialist mental health professionals in every secondary school, introducing free breakfast clubs in every primary school, and ensuring earlier intervention in mainstream schools for pupils with special needs.

“But we know poor behaviour can also be rooted in wider issues, which is why the government is developing an ambitious strategy to reduce child poverty led by a task force co-chaired by the education secretary so that we can break down the barriers to opportunity.”