The amount of novichok in a perfume bottle that killed Dawn Sturgess in 2018 was enough to kill thousands of people, the public inquiry into her poisoning has heard.

The 44-year-old died after she “unwittingly applied” the nerve agent to her skin following the discovery of the container in Amesbury, Wiltshire, in July of that year, Andrew O’Connor KC told the hearing.

The Dawn Sturgess Inquiry, which opened on Monday and is expected to last until December, aims to establish the circumstances of her death, who was to blame and what lessons can be learnt.

Mr O’Connor, counsel to the inquiry, opened the proceedings by describing Ms Sturgess as an innocent member of the public who had been caught in the “crossfire of an illegal and outrageous international assassination attempt”.

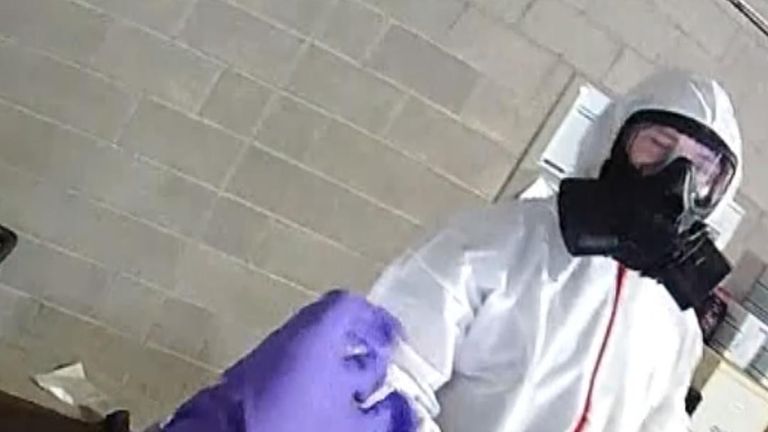

It is believed the perfume bottle containing the novichok was dumped by members of Russia’s military intelligence squad after they attempted to murder former spy Sergei Skripal in nearby Salisbury four months earlier.

The two men are alleged to have smeared the nerve agent on Mr Skripal’s front door handle.

Mr Skripal, his daughter Yulia and police officer Nick Bailey, who attended the scene, all fell ill after being poisoned but survived – as did Ms Sturgess’s partner Charlie Rowley.

He found the bottle, which was contained in packaging suggesting it was Nina Ricci Premier Jour perfume, and gave it to Ms Sturgess.

The inquiry heard she felt “peculiar” shortly after spraying it on herself and went into the bathroom – where her partner then found her “convulsing and drooling at the mouth”.

She was rushed to hospital, but never regained consciousness.

‘Caught in the crossfire’

Mr O’Connor said: “It’s no exaggeration to say the circumstances of Dawn Sturgess’s death were extraordinary, they were indeed unique.”

He described her as living a life that was “wholly removed from the worlds of politics and international relations” but that “she had been caught, an innocent victim, in the crossfire of an illegal and outrageous international assassination attempt.”

Addressing the inquiry’s chairman, former Supreme Court judge Lord Hughes of Ombersley, he added: “Whether or not that is in fact what happened will, of course, be for you to determine.”

‘Entirely unaware of the mortal danger’

Following the poisonings, an international arrest warrant was issued for the two alleged attempted assassins, along with a third alleged accomplice.

However, Russia does not allow the extradition of its citizens, and it is thought unlikely the trio will ever stand trial.

Mr O’Connor said a “particularly shocking feature” of Sturgess’s death was that she “unwittingly applied the poison to her own skin”.

He added: “She was entirely unaware of the mortal danger she faced because the highly toxic liquid had been concealed – carefully and deliberately concealed – inside a perfume bottle.

“Moreover, the evidence will suggest that this bottle – which we shall hear contained enough poison to kill thousands of people – must earlier have been left somewhere in a public place, creating the obvious risk that someone would find it and take it home.

“You may conclude, sir, that those who discarded the bottle in this way acted with a grotesque disregard for human life.”

Read more from Sky News:

Girl’s father ‘told police he killed daughter’

Thousands denied weight loss jab

Woman died due to ‘defective’ bed

Ms Sturgess suffered from long-term alcohol dependence but was said to be “settled and happy” in the months before her death.

Inquest to address key questions

Mr O’Connor said a key question for her family was why doctors initially thought she may have been suffering from a drug overdose when she was taken to hospital after being poisoned by the nerve agent.

He added they wanted to know “whether any of the things that may have gone wrong in Dawn’s treatment could have made a difference to her chances of survival”.

Michael Mansfield KC, counsel on behalf of Dawn Sturgess’s family, told the hearing that local police were forced to rely on Wikipedia for information on how to respond to the poisonings.

He said that documents showed public health bodies were concerned that “secrecy, withholding of relevant information and an over-centralisation of decision-making in central government hampered the response” and in the early stages it was “very difficult” to access credible information

Mr Mansfield also said the attempted murder of Mr Skripal was “no bolt from the blue” and it was important to explore “If the attack could and should have been prevented by the UK authorities”.

He added: “Was there a failure to prevent a chemical weapons attack on UK soil? Were countless members of the public put at risk, with the potential for hundreds or even thousands of deaths?”

Mr Skripal served as a member of Russian military intelligence, the GRU, but was convicted in Russia on espionage charges in 2004 after allegedly spying for Britain, the inquiry heard.

He was sentenced to 13 years in prison, but in 2010 he was given a presidential pardon and brought to the UK on a prisoner exchange before settling in Salisbury.

The Skripals will not give evidence at the inquiry due to safety concerns.

The inquiry continues.